It’s the last month to discover and share our 2016 community art show, “In Layers: the Art of the Egg” https://www.facebook.com/events/305884369763841/ Visit soon!

New in exhibit! male Common Merganser carving

We’re pleased to add the male Common Merganser to our Spring Wetland exhibit! Thank you, woodcarver Dick Allen! http://ow.ly/i/hBwIl

Season’s Tweetings

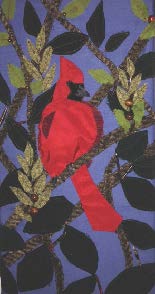

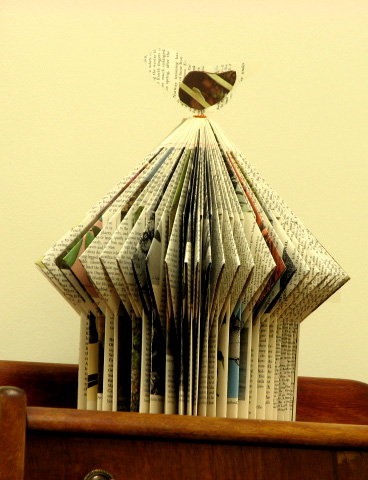

Art of Birds, clockwise from upper left: needle-felted Owls (Susi Ryan’s class); Flood Birds (carved by David Tuttle from trees washed out during the 2013 flood); Eagle quilt (Carol McDowell for the Birds of a Fiber exhibit); Northern Parula (wood carving by Bob Spear); Scarlet Tanager ornaments (carved by Dick Allen and painted by Kir Talmage); Wren (carving by Elizabeth Spinney)

The Art and Artists of “Birds of A Fiber” (2015 Community Art Exhibit)

In selecting art for the Birds of a Fiber exhibit, we hoped to allow the variety of media to hint at the diversity of birds. We had hooked rugs and traditional penny rugs, photographs rendered in cross-stitch, crocheted and fabric sculptures, needle felted miniatures, multimedia collages, paper sculpture, and quilts.

We hope you had a chance to see some of these works for yourself! There is not enough room to show all the works here in our mini slideshow. However, all the artists are listed below.

- Ann Wetzel, penny rug

- Carol McDowell, quilted art

- Dawn Littlepage, textile collage

- Elizabeth Spinney, crochet

- Erin Talmage, recycled paper

- Eve Gagne, cross stitch

- Kir Talmage, needle felted wool

- Marya Lowe, quilted art

- Morgan Barnes, needle felted wool

- Robin Hadden, rug hooking

- Katherine Guttman, mixed media (fiber, glass, and metal)

- Nancy Tomczak, mixed media (fiber and watercolor)

- Girl Quest participants, fiber birds/mixed media

The Bird Carver’s Daughter (Part 8: My Dead Arm)

Guest post by Kari Jo Spear, Photographer, Novelist, and Daughter of Bob Spear

This post appeared first in our late summer 2014 issue of Chip Notes.

My arm was killing me. Every muscle burned, my fingers cramped, and my shoulder barely fit in its socket any longer. In other words, I was in agony, and it was all my father’s fault. I was furious with those stupid birds of his and his stupid idea about carving every freaking bird that had ever been stupid enough to set its freaking feathers in Vermont. And I was mostly mad about his stupid idea to rebuild the barn on the old foundation next to Gale’s house and keep his stupid birds in there.

I was going to be maimed for life because of this! I was never going to be able to use my right arm again. My fingers were ice cold and I could barely feel them, much less move them. Any doctor would agree this was child abuse. I should be put into foster care and live in a nice, normal apartment in a city and never have to look at another bird again as long as I lived!

And not only that, my hand was sticky, and I hated that more than anything.

But I forced my smile back on. “And what would you like?” I asked a sweet little girl standing in front of me.

“Chocolate, please,” she said with an eager light in her eyes.

“Chocolate it is, then,” I said, and bent over the cooler again, trying to hide my pain.

I had been scooping ice cream for three hours. It had seemed like a really good idea at first. My father was hosting his first open house. It had been advertised all across the media. His “project,” now officially called the Birds of Vermont Museum, was open for visitors. In reality, today’s open house was a test to see if anybody was interested. To see if anybody was insane enough to make the drive all the way out to Huntington to see a bunch of wooden birds. Of course, there was no charge. We were still ages away from having all the permits and stuff that were required to become a business, even one not for profit.

To sweeten the deal, my father was offering a free dish of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream to everybody who showed up that day. For some stupid reason, the ice cream gurus had donated a bunch of bottomless cardboard tubs of the rock hard, icy, sticky stuff for the occasion. And for some stupid reason, I’d thought that was really nice of them and volunteered to be in charge of it.

And now my right arm was totally dead. I didn’t think anything could ever make me hate chocolate. But this afternoon was doing a good job of it.

“Here you go.” I handed the little girl her dish and dragged my eyes to her mom. “And for you?”

“Vanilla, please,” she said.

I decided to hate vanilla, too. I made my poor, abused fingers close around the scoop that lived in the vanilla tub.

“And how were you lucky enough to rate this job?” the mom asked.

I looked up at her as though she were out of her freaking mind. Beyond her, the line of people reached across Gale’s kitchen, down the hall, out the front door, along the path, across the driveway, and down the side of the road all the way to the shop. Which we were now supposed to call the Freaking Birds of Vermont Museum.

“I’m his daughter,” I growled.

“Oh, how marvelous! Your father has such incredible talent! Such patience! Such vision.”

I looked at her again to see if she was sane or not.

“To create such a project! And not want to make any money at it! All that work, to educate people about nature and conservation and – oh, everything! I had to come up here the minute I heard about it. This is something that must happen. I wanted my daughter to be able to say she’d seen it in its earliest days.” She nodded at the little girl dripping chocolate all over the place, who nodded back vigorously. Then the mom looked back at me. “You are so lucky to be part of all this.”

I looked up at her, my arm suddenly feeling a little less leaden and sticky. Did she really mean she hadn’t come all this way for free Ben and Jerry’s?

“I mean, look at the turnout!” she said. “There are hundreds of people here. You must be so proud.”

“It’s amazing,” someone behind her said.

“They look alive,” someone else said.

“I’m going to start a life list,” another voice added.

No, don’t! I almost said aloud. It won’t lead to good things! But then I found myself really smiling as I handed the mom her little dish. “Here you go,” I said. “Thanks so much for visiting the Birds of Vermont Museum today. And what kind would you like, sir? We have chocolate and vanilla and suet with sunflower sprinkles. Just kidding,” I added.

He laughed. “Chocolate, please.”

“Coming right up. Don’t let it drip on your binoculars.”

Everyone laughed. What great people, I thought. What a momentous day!

And what big muscles I’m going to have.

Kari Jo Spear‘s young adult, urban fantasy novels, Under the Willow, and Silent One, are available at Phoenix Books (in Essex and Burlington, Vermont), and on-line at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Previous posts in this series:

Part 1: The Early Years

Part 2: The Pre-teen Years (or, Why I’m Not a Carver)

Part 3: Something’s Going On Here

Part 4: The Summer of Pies

Part 5: My Addiction

Part 6: Habitat Shots

Part 7: Growing Up

The Bird Carver’s Daughter (Part 7: Growing Up)

Guest post by Kari Jo Spear, Photographer, Novelist, and Daughter of Bob Spear

Things were starting to get out of hand.

My father’s carvings had been well received during their debut in the art gallery in Montpelier. People had flocked in to see them. Photos had been taken. Articles had been written. In short, Vermont was interested in his project. After their few weeks in fame and glory, my father returned his carvings to his shop in triumph.

The problem was, they seemed to have grown while they’d been gone. Or else the shop had shrunk. The first day they were back, I stood in the doorway, surveying the long, rectangular room. Or trying to survey it. I couldn’t really see it, or the bench, or the wood stove, or any of my father’s tools. Or my father, for that matter, and even in his younger days, he wasn’t hard to miss. (Meaning that he wore red shirts back then, too, of course! I don’t mean to imply anything about his general recognizable shape.)

The whole room was full, as far as I could tell, of green, leafy branches, tree trunks, and bright spots of plumage.

“I’m back here!” My father’s voice came from somewhere near the window. I turned sideways and squeezed between Plexiglas cases in his direction, stopping to glance at my favorites — the red-winged blackbirds. Yup, the mud I’d painted down at the bottom still looked good.

I finally found my father sitting on his stool, peering in my direction.

“You made it,” he said.

“Yeah, it’s getting a little tight in here. What’d they feed these guys in Montpelier, anyway? Did they put steroids in the suet, or something?”

My father didn’t laugh. “I’ve been talking to the Shelburne Farms people. And the Ethan Allen Homestead.”

“About?” I prompted.

“Housing them,” he said. “The collection.”

So he’d evidently noticed the overcrowding of the avian population in the room, too.

“What are they thinking?” As tight as it getting in here, I suddenly felt kind of funny about the carvings all going away permanently. I’d kind of missed them just while they’d been off on their maiden flight. And would strangers take good care of my mud, and everything? I mean, that mud was the first and only mud I’d ever painted! It wasn’t just any mud, after all. It was part of my childhood memories.

“No one seems to think they’ve got enough room.”

“Are you kidding me? Those barns at Shelburne Farms are huge!”

My father cleared his throat and said something that sounded like “…more cases, and a wetland diorama, and endangered species…”

I blinked. “You mean, there’s going to be lot more? A lot more?”

My father looked kind of sheepish and muttered something about investors and interested parties. I didn’t know much about that kind of thing, but I knew that he was talking about money. For the first time, I began to realize that this project might get really, really big. And not only that, it might really happen.

‘Holy cow,” I said. “Are you like going to get famous?”

My father suddenly looked horrified and leapt off his stool. “Let’s go canoeing,” he said in a rush, and he was gone as though he’d grown wings himself.

It took me a lot longer to find my way to the door of the shop. Something in the atmosphere had suddenly changed. I looked at the cases and the birds inside them in a new way. Yeah, they were bigger all right. Even my mud didn’t feel as though it was all mine any longer. Whatever was starting to happen here might get really weird, like turn into a legacy or something. And outlast my father.

And even me.

Kari Jo Spear‘s young adult, urban fantasy novels, Under the Willow, and Silent One, are available at Phoenix Books (in Essex and Burlington, Vermont), and on-line at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Previous posts in this series:

Part 1: The Early Years

Part 2: The Pre-teen Years (or, Why I’m Not a Carver)

Part 3: Something’s Going On Here

Part 4: The Summer of Pies

Part 5: My Addiction

Part 6: Habitat Shots

Call to Artists: Perilous Passages

The Birds of Vermont Museum seeks artwork for an exhibit commemorating the Passenger Pigeon. In the 100 years since the last Passenger Pigeon died, a deeper and more passionate comprehension of extinction compels us to conserve and protect. The Museum’s exhibit intends to highlight different aspects of the Passenger Pigeon’s story and its consequences. If you have (or will be making) art that speaks to this, please let us consider your work for our exhibit.

The exhibit will be a part of Project Passenger Pigeon’s 2014 centenary observation of the extinctions of the passenger pigeon. It will be open from May 1 – October 31 at the Birds of Vermont Museum (http://www.birdsofvermont.org). For more on the project: http://passengerpigeon.org/

How to submit: send up to 3 digital images (by link to your online portfolio or attach a JPG) to museum@birdsofvermont.org . Recommended size: about 800-1600 pixels on the longest side. Deadline for submission: March 15. Artists will be notified between March 16 and 31. We will be hanging the art between April 15-30.

If you are interested in selling your art (or cards/prints) during the exhibit, please let us know that as well.

The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds of Vermont

Guest post by Kir Talmage, Outreach and IT Coordinator for the Birds of Vermont Museum. This article also appeared in the Vermont Great Outdoor Magazine.

The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds of Vermont is out! As you likely know, an Atlas is

The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds of Vermont is out! As you likely know, an Atlas is

a : a bound collection of maps often including illustrations, informative tables, or textual matter b : a bound collection of tables, charts, or plates (Merriam-Webster)

This meager definition masks the huge intention and effort that goes into the creation and revision of an Atlas. This particular Atlas is the product of a state-wide breeding birds research project that has spanned ten years, brought together some 57,000 observations, and drew on 350 volunteers. It epitomizes a successful citizen science project. The data (observations) were pulled together by Vermont Center for Ecostudies into one beautiful reference book, which was published in April of this year. The completed Atlas—with maps, individual species accounts, discussions of Vermont’s habitat and land use changes, and analyses of the data—has already helped scientists and policy makers decide how best to work and plan for avian conservation. Continue reading “The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds of Vermont”

Special Carving Exhibit: Birds by Peter Padua

The Museum is showing the work of Peter Padua, a 90-year old Middlebury resident and woodcarver. An article by John Flowers (for the Addison Independent last November) paints a picture of a dedicated woodcarver with a passion for natural inspiration and materials and an eagerness for new challenges.

Sounds a bit like Bob Spear don’t you think? These life-long carvers have followed similar paths at times too, brightening many homes and outlooks through their talent and efforts.

Padua was a New Jersey high school senior in wood shop class when he felt moved by a photograph of a deer to try his hand at carving its image. His instructor encouraged Padua’s interest. After a few months of careful work, he produced his first piece: a small, expressive deer.

Padua’s future lay in work as an engineering draftsman, but he made time during lunch breaks and off hours to add to his growing collection of fish, bears, Christmas holiday ornaments for his three children, and birds, including representations of all of the state birds.

Padua’s workshop occupies a portion of his basement where his tools suggest an evolution of technique, style, and technology over the years. Basswood is his medium of choice. Padua officially retired twenty-five years ago, yet allows very few days to go by without spending time on or with his carvings. He is very excited about sharing his work with the Birds of Vermont Museum’s visitors and we are delighted to bring it to you. Please come and enjoy!

Exhibit dates are May 1–October 31, 2013.

The Bird Carver’s Daughter (Part 6: Habitat Shots)

Guest post by Kari Jo Spear, Photographer, Novelist, and Daughter of Bob Spear

“Take a shot in that direction.” My father pointed down toward the brook through some hemlock trees. “Good ruffed grouse territory.”

“Okay,” I said. My job was to take an interesting photo. So I crouched down, trying to get into ruffed grouse mode, going for an eye level perspective. If I was a grouse, I’d lay my eggs right under the trees. Of course, I wasn’t a grouse, and this was another of my father’s crazy attempts to get me into his “carve all the birds in Vermont” project. He thought it would be helpful to have a plastic sleeve hanging from each display case with some facts about the bird and a photo of its nesting habitat. I thought all the leaves and flowers and stuff he was putting in the cases would be enough to clue people in, but he wanted photos, too. Wouldn’t it be nice if I took them?

Well, I liked taking photos, and my father’s fancy Nikon with interchangeable lenses was pretty cool. But nesting habitat was not exactly an exciting subject to photograph. We’d been hiking for hours, and I’d been dutifully taking shots of deciduous trees, evergreens, moss, and even dead stumps. That part wasn’t really so bad. The real problem was that habitat shots had to be taken in the spring when the birds were nesting. The birds needed to take advantage of insects, who were also doing their multiplying thing. Right now, every black fly in Huntington was taking advantage of their favorite food source—me. They didn’t care about my artistic endeavor, they didn’t care that I reeked of insect repellant, and they didn’t care that I was allergic to them. My eyes were going to be puffed shut tomorrow, I knew it.

I am a grouse, I thought. I snapped two more shots down toward the brook, even climbing into the brush to get a nice, curving limb to frame the top.

“Okay,” my father said. “Now I want to go to a farm up the road. There’s a pair of cliff swallows building under the eaves of the barn. We can get barn swallow habitat inside. And all the apple trees are in bloom. They’re real pretty, and they’d be good blue bird habitat.”

Anything to get away from the buggy brook. I swatted my way out of the woods—flies never seemed to bother my father—and scratched my way up the road to an old farm that looked as thought it had been there since the glaciers moved out. I liked the way the buildings nestled into the hillside. Sure enough, there was a small colony of cliff swallows building their funny little jug-like nests under the eaves. I didn’t even ask how my father had known they were there. While he chatted with the farmer, I photographed the eaves, then some rafters inside where some barn swallows were busy irritating the cows, and then I wandered around the apple trees in full bloom and thought about how nice a big bee sting would look right between my puffy eyes. Maybe some poison ivy to set it off. Then I tripped over a branch buried in the new spring grass and landed in a woodchuck hole, twisting my ankle.

My father got the car and drove me home. Fortunately, I wasn’t bleeding—my father was not good with blood—and the camera was okay, so there was no harm done. “An old war horse,” my father said, seeing me looking at it on the seat between us.

I didn’t think he was referring to me. A young warhorse, maybe.

“You may as well keep it,” he added.

“Until next weekend?” I asked, wondering if my ankle would be up to more traipsing around.

He kind of shrugged. “Till whenever. If I need it for something, you can bring it back.”

“Oh,” I said, it slowly sinking in that he’d just given me a really nice camera. On a kind of permanent borrow.

“Might as well take the lenses, too.” I noticed that they were in the back seat. A 300mm lens and a wide angle.

“Thanks,” I said, meaning it.

“It’s a good camera,” he said. And that was that. Then he added, “But we need to get the film developed right away.”

“What’s the rush?”

“Montpelier.”

Right, I thought. The state capital.

“Library,” he added.

“You’re going to carve books next?” I’d believe anything.

He shot me a look. “No. Going to have the carvings there next week.”

“What?”

“There’s an art gallery upstairs in the library,” he said patiently. We’re going to have a big opening. Newspapers will be there.”

I looked at him, wondering how he’d known how to set up something like this. He’d probably enlisted Gale. He didn’t even look nervous. I’d be frantic.

“We’ve got to start getting people interested in the project, you know,” he went on. “Need to find someplace to house them.”

At the rate he was carving, he wasn’t going to have room to breathe in the shop much longer.

“There’ll be a reception. With food.” He looked at me hopefully.

“Of course I’ll be there,” I said. And not just for the food.

“Good,” he said. And then he smiled, just a little. “It’s upstairs. Your ankle will be better by next weekend, right?”

Of course it would be. Who wouldn’t want to get all hot and sweaty lugging bird cases to an upstairs gallery? I heaved a sigh. I’d never figure out how he managed to talk me into getting deeper and deeper in this project of his.

The next morning, I limped into school with my eyes puffed mostly shut, my arms and legs sunburned and dotted with red spots, and my left ankle wrapped up.

“What happened to you?” my homeroom teacher asked. All around us were kids with honorable injuries, acquired by heroically sliding into home plate or after bursting through a finish line. Everyone turned to me, waiting to hear my glorious tale.

I dropped into my desk with a sigh. “Wood chuck hole.”

Everyone’s eyebrows went up.

I nodded wisely like this was a big deal. Lowering my voice, I said, “Okay. Let me tell you guys about… habitat shots.”

Author’s Note: Visitors to the museum will notice that there are no photographs hanging from any of the cases. My father finally realized, as someone had tried to tell him, that people would get the idea where the birds nested from all the leaves and flowers and stuff in the cases. The habitat shot phase passed quickly, but to this day if I take a photo with no apparent subject, my father will look at it, smile a little, and say, “Looks like a habitat shot to me.”

And I still have the camera, tucked away somewhere safe. Permanent borrow: thirty-five years and counting.

1981, Photographer unknown

Kari Jo Spear‘s young adult, urban fantasy novels, Under the Willow, and Silent One, are available at Phoenix Books (in Essex and Burlington, Vermont), and on-line at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Previous posts in this series:

Part 1: The Early Years

Part 2: The Pre-teen Years (or, Why I’m Not a Carver)

Part 3: Something’s Going On Here

Part 4: The Summer of Pies

Part 5: My Addiction